Robert McKee’s “Works/Doesn’t Work” Review

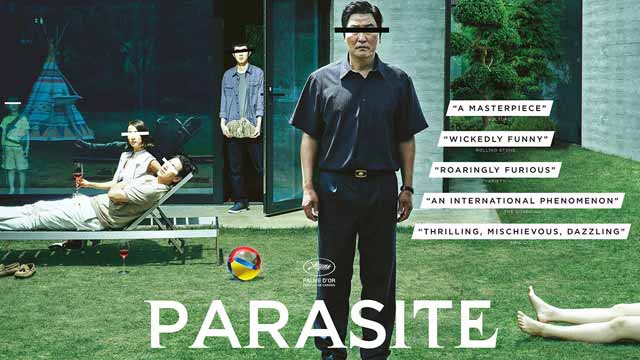

PARASITE

Written & Directed by Bong Joon-ho

It Works. (Spoiler Alert!)

In this “Works / Doesn’t Work” review, I’ll take up the question every filmmaker with global ambitions asks: What makes an international hit? What does the world want? The answer is two forms of pleasure: New knowledge and an old mirror.

New Knowledge

PARASITE serves this anthropological pleasure wrapped in a sharp-edged satire of Korean class warfare. This dark farce comes complete with plot-convenient overhearings, bizarre coincidences, bloodbath violence and a traditional yet fantasied happy ending. But that’s not what won this absurdist tale all those awards. The film’s genius is in its cast and their never-seen-before traits.

For example: The olfactory powers of the rich in this film are so acute they can sniff out subterranean odors on people who live in basement apartments or ride the subway. The servants are so talented at improvisation they can impersonate any white-collar PhD and so skilled at IT they can forge credentials to prove they are who they say they are.

PARASITE is a modern retelling of the clever-servant/dim-witted-master tale. These stock characters have been around for over two thousand years, first on stage in the Greek comedies of Menander (342-290 BC) and the Roman satires of Plautus (254-184 BC), then cast in the farces of the commedia dell’arte and Shakespeare through to P. G. Wodehouse’s Jeeves and Wooster and Kathryn Stockett’s housekeepers in The Help. Now Bong Joon-ho gives us a 21st century example, sending his con men and women into a wealthy but daft family by posing as highly skilled professional servants.

PARASITE is uniquely specific to its culture and yet universally human.

A Mirror

And the one thing everyone in the world feels is underdog-nicity. No matter who they are or where they stand in their society, everyone feels that they are up against powerful negative forces that block them from getting what they want out of life: Economic and job competition, government regulations and taxes, family squabbles, loneliness, health problems and never enough time.

PARASITE’s protagonists are the most loveable underdogs in decades. They live squashed under the bottom rock in society’s pyramid of power. Their basement apartment sits at the end of an alley where local drunks relieve themselves and a flood fills their home neck deep in sewage. Nonetheless, they are not bitter. The Kim family keeps their heads up and soldiers on, simply wanting a spot to steal Wi-Fi.

The international audience has made their empathetic connection and now PARASITE will burrow its way into their hearts.

That’s the key: culturally specific, universally human.