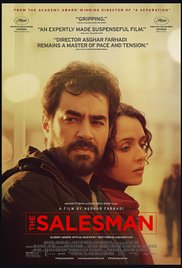

Robert McKee’s WORKS / DOESN’T WORK Film Review:

The Salesman (2016) | Written and Directed by Asghar Farhadi

McKee Says: It Works (Spoiler Alert!)

MERGED GENRES:

Definition: A story’s genres merge when each genre supplies the other’s motivation.

Iranian filmmaker Asghar Farhadi’s genre of choice is Domestic Drama. The positive/negative charge of the core value in family stories veers between Unity and Disunity and back again, raising the question: Will this family stay together or split apart? Farhadi’s films—ABOUT ELLY (2009), A SEPARATION (2011), THE PAST (2013)—all feature fragile families conflicted on two levels: inwardly into themselves and outwardly into their cultures.

His most recent work, THE SALESMAN (2016), merges its Domestic Drama with a second genre, the Crime Story. In this case, rape. As the film begins, a stranger enters the protagonist’s apartment and violates his wife. The neighbors, however, doubt her story. Their wordless suspicions inflict a bitter humiliation, so she decides to drop the matter and not call the police.

Her husband chooses instead to pursue revenge. He secretly hunts for the rapist, planning to punish him, not with the law, but with exposure to his own family. In Iranian culture, a dirtied reputation in the eyes of your family is crucifixion worse than prison.

Just as the protagonist is about to exact revenge, his wife intervenes and threatens to leave him. She fears that if her husband punishes her attacker, his actions will expose her to even more disgrace. Like the rapist, the victim’s greatest fear is shame. To prevent that, she puts her marriage in jeopardy.

TURNING POINTS:

Iranian culture is not only high context* (see below), and therefore dialogue-lite, but governed by behavioral restraints and moral adhesions absent in western culture. As a result, the actions of the wife and husband trigger reactions from their society and within their marriage that deliver surprise after surprise, followed by insight after insight. The storytelling might not amaze a Persian audience, but for this American, every turning point came with a jolt. The Crime Story climaxes in a state of chaotic Justice I did not see coming.

CHARACTER ARCS:

The conflict-filled path through this story exposes and changes the humanity of both husband and wife. What they lose in innocence, they gain in self-awareness. And since the couple works in a theatre troupe, the change may make them more mature actors. But given the guilt that will now haunt their lives, this is an arc they could have done without.

*High-context cultures have a strong sense of history and tradition. They change very slowly over time, and so from generation to generation their members hold many beliefs and experiences in common. A high-context culture will be relational, collectivistic, intuitive, and contemplative. It places high value on interpersonal relationships within a close-knit community.

As a result, within these in-groups many things can be left unsaid because their members easily draw inferences from their shared culture and experiences. The Italian mafia is such an in-group. In THE GODFATHER, when Michael Corleone says “My father made him an offer he couldn’t refuse,” an entire episode of extortion becomes violently clear. Michael then goes on to make the event explicit to Kay Adams because she’s not in the in-group.

High-context cultures, such as those in the Middle East and Asia, have low racial and social diversity. They value community over the individual. In-group members rely on their common background, rather than words, to explain situations. Consequently, dialogue within high-context cultures calls for extreme economy and precise word choices because within such settings a few subtle words can implicitly express a complex message.

Conversely, characters in low-context cultures, such as Northern Europe and North America, tend to explain things at greater length because the people around them come from a wide variety of racial, religious, class, and nationalistic backgrounds. Even within the same general cultures these differences appear. Compare, for example, two American stereotypes: a Louisianan (a high-context culture) and a New Yorker (a low-context culture). The former uses a few tacit words and prolonged silences, while the latter talks frankly and at length.

Excerpt from Dialogue: The Art of Verbal Action for Page, Stage, and Screen (P. 187)